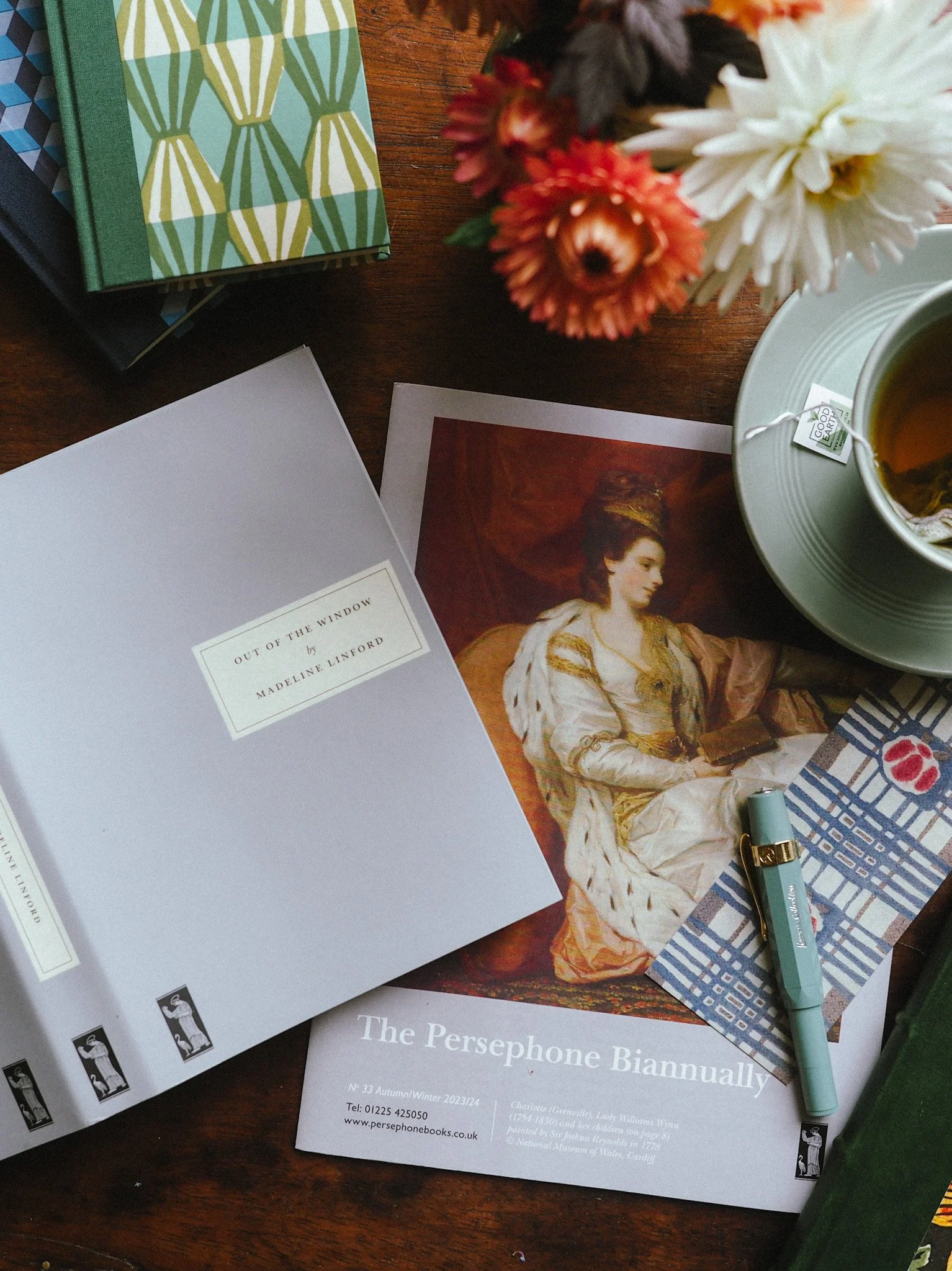

Out of the Window by Madeline Linford

First published in 1930, and newly reprinted by Persephone Books, Out of the Window* by Madeline Linford was a novel ahead of its time and quietly daring in its exploration of whether sexual attraction alone can be the mainstay of a marriage.

By chance, Ursula Fielding, the adored only child of an affluent, middle-class family meets Kenneth Gandy, a young engineer from Manchester, at a dreary party on a chill February evening. Ursula is immediately drawn to Kenneth’s good looks, and over the following few months the pair fall in love and marry, ignoring the disapproval of both families. Once the honeymoon is over, however, Ursula must face the realities of housekeeping on a very small budget.

One of the reasons I enjoyed Out of the Window so much is because it explores many of the themes in which I have a particular interest (and which are common to many other Persephone books). Houses, and women’s role in the home, are significant in this book, and gardens and nature (or lack thereof) also play an important role in signalling class distinctions and women’s lack of freedom.

At the start of the book, Linford describes the childhood homes of the two lovers in careful detail, highlighting the huge contrast between their backgrounds. Ursula lives with her father (a prosperous doctor), mother and spinster aunt in a large, comfortable house (where a cook and maid are employed) situated in an attractive village in ‘the smooth green spread’ of Cheshire. Their home is surrounded by the ‘orderly lawns and flower beds’ of their neighbours and ‘a few scattered farms’ on the verdant horizon.

Kenneth’s setting is urban, living with his mother in a cramped home, where the kitchen floor oozes patches of damp in wet weather and a constant battle is waged against the dirt of the street and the city air grimed with coal dust. A few ‘wan, emaciated’ trees struggle for existence in the street outside, but Kenneth is proud of his home and congratulates himself on a lifestyle that ‘envious neighbours considered to be affluence.’

Ursula takes the ease, comfort and surrounding beauty of her life - previous to her marriage - entirely for granted.

It’s easy to guess that Kenneth and Ursula’s marriage is doomed from the start, but Linford probes the breakdown of their relationship with a skilled hand. In describing the respective houses of Kenneth and Ursula’s upbringing, Linford cleverly shows that the home in which the newly wed couple start their lives together will be perceived very differently by each of them. Indeed, it is this home - coupled with her inexperienced naivety - that is in many ways Ursula’s undoing.

Unusually for the time in which she wrote, Linford does not rule out the couple’s compatibility based on social class alone; instead she offers a bleak depiction of the realities of poverty compared with the ease of wealth. The grim toil of Ursula’s domestic work, coupled with her unequal status within the home, strains her marriage.

Ursula, with her privileged if not spoiled background, has no idea how to handle a small budget or how to cook frugal, but satisfying, meals. She finds the constant housework a drain on her energy and spirit, and her home with Kenneth is described as a kind of prison in Ursula’s eyes. To Kenneth, their house, situated within the suburban Fothergill Estate of five hundred houses, is a source of considerable pride: full of every convenience and easy to manage.

Ursula, once free to drive her father’s car about the countryside and to visit friends, finds herself forced to stay home: she no longer has use of a car and must consider the expense of every outing. Also, her housewifely duties and Kenneth’s demands (he’s furious when she goes out for dinner with a friend one evening) tie her to home. When Ursula isn’t struggling with burnt meals and charred pots, she’s generally mending or cleaning. Dorothy Parker’s line — trapped like a trap in a trap — rang through my head several times whilst reading Out of the Window.

It’s not only her husband who judges Ursula’s housekeeping abilities: their neighbourhood and home are governed by the strict rules of the Estate, which are overseen and enforced by the prison warden-like Miss Lucas, who calls once a week for the rent and to inspect and critique Ursula’s housekeeping.

Miss Lucas even extends her criticism to the garden, and insists that Ursula plant some seeds in the spring. Kenneth scoffs at gardening as ‘a woman’s game,’ and so an already overworked Ursula is deeply resentful as she sows a few twopenny packets of seeds with ‘a despondent conviction that she was wasting her money and they their energy. It seemed very unlikely that the things which grew so happily in the garden at home would be content with the smoke and poverty of the Fothergill Estate.’

Like the seeds, Ursula wilts and withers in her new surroundings, and Linford signals Ursula’s unhappy state when she is unable to enjoy the outdoors. The reality of her impoverished circumstances first hits Ursula when she opens a window to try to freshen up the air in a room. The breeze that gushes through the window carries with it the overpowering cooking smells from her (very close) next door neighbour’s kitchen, and she shuts the window again. Trapped like a trap in a trap.

Windows, like houses, are important in this book: they highlight the contrast between Ursula’s childhood, when windows framed attractive garden scenes and let in sweet-smelling country air, and her married adulthood where windows are firmly shut against smells, noise and dirt and offer no pleasant view.

I’m always interested in how writers describe the seasons, and in Out of the Window, Linford references the shifting months and transitions in nature very deliberately. It is significant that the novel starts in February, with the first snowdrops poking through the ground, just as Ursula’s sexual awakening arrives in the form of Kenneth. And it is in the luscious, carefree days of summer that their relationship cements and they become engaged. It is not by chance that Ursula and Kenneth fall in love in the summer months: it is in this season that they are able to meet out-of-doors, rather than in Ursula’s home, where Kenneth was constantly aware of their differing backgrounds. Nature offers a common ground in which they may meet as equals, and they are able to visualise a shared life together as a result.

As their wedding takes place in October, however, the ‘fragile roses of autumn, waiting in resignation for the first touch of frost’ foreshadow trouble ahead, and it is in the bitterly cold days of winter, living in a freezing house where the coal allowance is carefully budgeted and rationed, that Ursula and Kenneth’s passion first starts to cool.

At the start of her marriage, Ursula insists that mutual attraction is of paramount importance: rather than a common background and interests, she believes that ‘there has to be something else to make one want to marry a man. A sort of glow. I don’t know what it is. Passion, perhaps. It’s really more important than tastes in common, because it’s the thing that makes marriage worthwhile.’

Several months into the reality of being a housewife, however, Ursula has changed her tune. Confiding in her spinster Aunt Agnes, she says ‘...there ought to be some other solution for girls in love. It isn’t fair that they should be tied all their lives and have children, just because they once felt passionate about some man and were blind to everything else. The marriage service should be postponed until they had lived together for a while and the glamorous side of it had got less interesting.’

This latter speech of Ursula’s is the most important in the book, and can only be read by women in the twenty-first century with heartfelt appreciation that things have changed a good deal since 1930. Reading Out of the Window, however, still leaves the modern reader pondering: have the societal expectations placed on men and women, particularly in regards to housekeeping, work and child-rearing, changed enough?

*Please note: affiliate links are used for Blackwells. If you order a book from Blackwells using one of my affiliate links, I may make a small commission from your purchase, at no additional cost to yourself. I like to support Blackwells by linking to their website, as I’m a big fan of their flagship Oxford bookshop, and they offer reasonable overseas shipping. You in turn support my work by shopping through my affiliate link. Thank you!