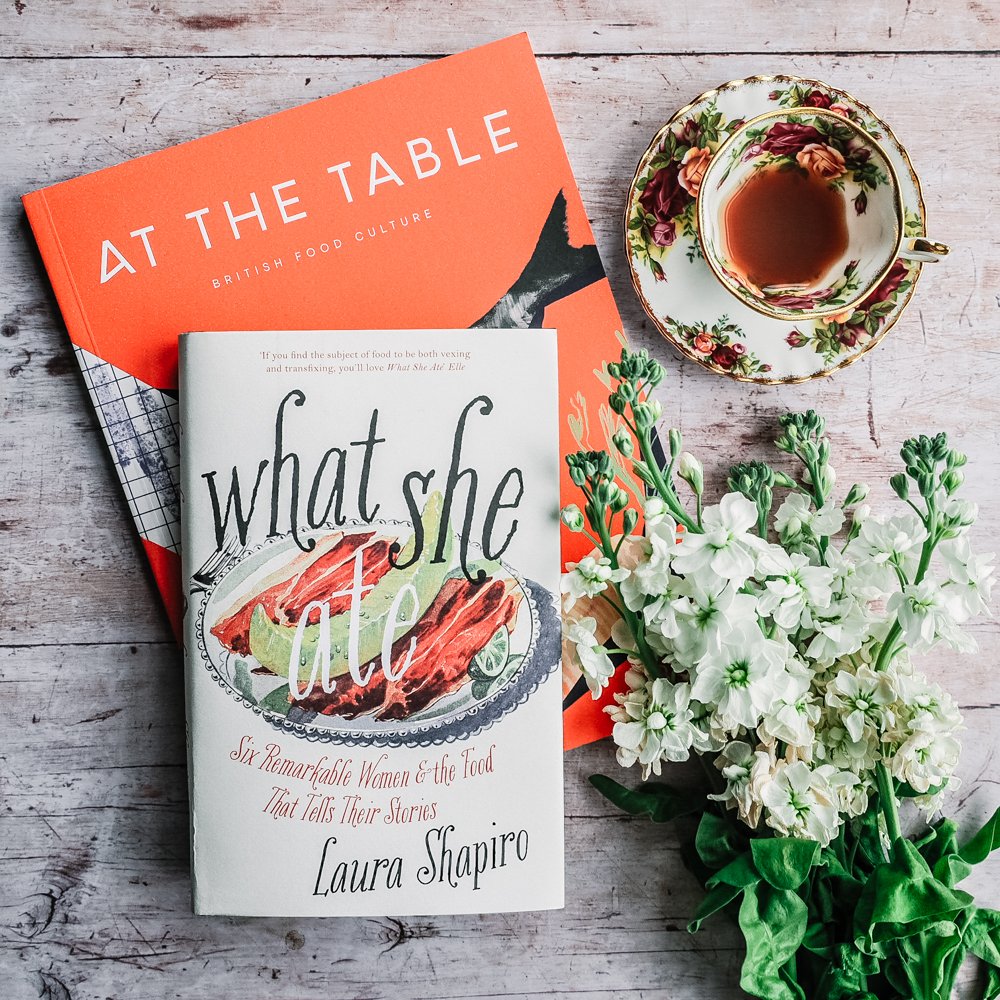

Laura Shapiro on Six Remarkable Women and What They Ate

One of the non-fiction books I've most enjoyed lately is What She Ate* by Laura Shapiro. As a journalist and culinary historian, Shapiro has long been fascinated by what a person's appetite says about who they are.

What She Ate explores the food stories of six very different women: Dorothy Wordsworth, devoted sister to her famous brother, William; Rosa Lewis, who cooked for the most distinguished of Edwardian society; First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt; Hitler's consort, Eva Braun; the British author Barbara Pym and Cosmopolitan editor (and chronic dieter) Helen Gurley Brown. These women were influential within the realms of literature, society or politics, but little else connects them, apart from a shared seat at the dinner table.

Laura Shapiro’s fascinating group biography highlights the complex relationship women have long held towards their meals, and shows that a person's food story is rarely straightforward. As someone with an eager interest in the domestic minutiae of people's lives, I found What She Ate a compelling read and was delighted when Laura Shapiro agreed to answer some questions about her book.

Laura Shapiro. Photo credit: Ellen Warner

MM: Would you tell me a little about yourself and your own food story?

LS: My mother was a wonderful cook -- she taught herself to cook after she got married, and became so good at it that eventually she started catering. My own cooking is much more haphazard, but what I did inherit was a fascination with food in all forms and at all times.

My favorite food memory from childhood is waking up early, the morning after my mother had catered a party, and going downstairs to find the refrigerator full of leftovers. She loved making hors d'oeuvres, so there were always lots of those packed up and put away -- "party rye" with onion, mayonnaise and parmesan, little cream puffs filled with crabmeat, sauteed mushrooms on squares of toast -- all cold, of course, and all so delicious. That is still my idea of a perfect breakfast, ideally eaten standing at the open door of the refrigerator in pajamas, picking out just what I wanted from each tidy package.

MM: In your book, you say ‘food talks’ and what a person does or doesn’t eat can say so much about them. In general, though, a person’s culinary history is largely ignored by biographers, even though all other aspects of famous people’s lives are examined under a microscope. Why do you think what people are cooking and eating so often gets left out of their personal histories?

LS: Traditionally, of course, food would not have been considered a dignified subject to include in the biography of a great man -- and great men were the ones people wrote biographies about. Food had to do with the body, it came from women's world or the world of servants, and it couldn't possibly have any significance beyond nourishment.

And the second reason, which today would now be the first reason, is that there's so little information out there. Until Instagram and food blogs came along, most people writing about their lives -- writing diaries, letters and memoirs, that is -- rarely mentioned what they were eating. So even if a historian or biographer is dying to know what someone ate, it's going to be very hard to find out.

MM: It was reading about Dorothy Wordsworth eating black pudding that first sparked your idea for ‘What She Ate.’ Would you explain why that particular meal interested you so much, and how you came to write your book?

LS: When I stumbled across the mention of black pudding in a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth, I couldn't believe my eyes. I knew a little about her, and nothing in that picture even hinted that she would eat such a thing. Her social class, her own cooking as she described it in the Grasmere Journal, her history of colitis -- black pudding for dinner would have been an affront to all of that. It was basically a sausage of blood and oatmeal, and although it had a longtime place on upper class breakfast tables, even that was starting to fade by the time this mention came along.

So I started to wonder, and I realized that if I could get a grip on this mystery, maybe I would learn something about Dorothy Wordsworth that I hadn't known before. Maybe food would give me access to someone's life in a new way.

MM: I loved a passage in your book when you wrote ‘our food stories...go straight to what’s neediest.’ You chose to examine women who in general had a complicated, and in some cases very insecure, relationship with food. How did you settle on which women to write about? Were you especially drawn towards food stories about women who saw food as troubling, more than delicious?

LS: So much of the food writing that's appeared in the last ten or twenty years -- popular writing, I mean, as opposed to scholarly -- is about the same thing: Food is love. Food is emotional support. Food brings us together. Of course all those things are true -- I've written them myself, many times -- but I really wanted to get to something else in this book. I think all kinds of things happen at the dinner table, and plenty of them are not about food-brings-us-together. So I chose women with complicated, hard-to-decode relationships with food, women whose food stories lurked below the surface.

MM: Do you think men and women eat in a very different way? Would men’s food stories be largely different from women’s?

LS: I'm absolutely positive men's stories would be different -- but I have no evidence for it at all. I do think women have an immediate and instinctive relationship with food that comes from a billion years of physical nurturing of babies, so that's one big difference between women and men, but I would never give myself the imaginative freedom to explore men's food lives the way I've always explored women's. For me, it would be like writing in a foreign language. There certainly are writers who can imagine other sexes -- in fiction and in non-fiction -- but for me it's difficult.

MM: During the majority of the history you wrote about in ‘What She Ate’, a woman’s place was very much considered to be within the domestic sphere, and yet many of the women you wrote about wielded food as a weapon to gain power in worlds beyond their kitchen. I thought it was especially fascinating to read about Rosa Lewis’s incredible career. Would you tell me a little more about how food completely changed her life?

LS: Rosa Lewis was an amazing example of a woman who made food her career for a very specific reason that I don't think had anything to do with food. She wanted to climb from working class to upper class, and she could see that in Victorian/Edwardian London, cooking would help her up the ladder.

What complicates the picture is that she didn't really want to change who she was. What she wanted was to be accepted at the top of the ladder as exactly who she was -- a former scullery maid named Rosa Lewis who could cook as well as Escoffier. And she succeeded, but only as long as she kept cooking. When she hung up her apron, after World War I, she lost her place on the ladder.

MM: Your book shows that there is a great deal of emotion - both positive and negative - attached to food, and yet Eleanor Roosevelt seemed most comfortable with food during her time at the White House when she could strip meal time from any emotive resonance and think of food as simply fuel for living. Why did she serve such dreadful food at the White House, and why did she seem to enjoy eating so much more later in life?

LS: Eleanor's story is very much about her marriage to FDR. After his affair with Lucy Mercer, she was devastated, and from then on their marriage was basically a political partnership. She shared his ideals, but what she couldn't bear was his luxury-loving side, the cocktails and fine meals and enjoyment of life that he had known while growing up and still relished when the workday was over.

That was the side of FDR that gave rise to his flirtatious attentions to other women and of course the affair with Lucy Mercer. She didn't want to feed that side of him -- literally, I believe. So she made no effort to change the terrible food served by the mean-spirited housekeeper she had hired. But when she was out of the White House -- travelling, or with her own friends, or pursuing her second career after FDR's death -- she was free to eat with pleasure.

MM: Two women in your book seemed to derive the most pleasure from food by simply not eating it at all. Would you tell me more about how a lack of food shaped the stories of Eva Braun and Helen Gurley Brown?

LS: These were, of course, the two dieters in the book. I hasten to add that they had nothing else in common, but they did share a fixation on staying slim. They felt very competitive with other women, and they desperately wanted to appeal to what neither of them knew yet to call the male gaze.

Helen Gurley Brown's single-minded focus on eating as little as possible throughout life did quite a bit of damage to her readers, since she was promoting an ideal of the female body that was unnatural and essentially unattainable. Eva Braun's effect on her moment in history was subtler but more terrible. Sitting at the table with Hitler and his entourage, she was so sweetly and stereotypically feminine that her presence created, in effect, a guilt-free zone for Hitler and his entourage.

MM: In terms of my own attitude towards food, I most identified with Barbara Pym. I liked the unpretentious, but still appreciative, approach she took towards food, both in her books and in real life. Would you tell me more about how the food she wrote about reflected the world around her?

LS: Barbara Pym had a wonderfully healthy relationship with food -- she just loved it, and it caused her no problems whatever as far as I can see. When it was delicious, she enjoyed eating it, and when it was awful, she enjoyed thinking about it. When she started on her life as a novelist after World War II, a whole spectrum of food was spread out in front of her -- tinned soups and flabby blancmange, and perfectly roasted duck with peas from the garden.

All of it went into the books, which is why it's possible to read her novels as a revisionist history of British cooking after the war. Pym was no fantasy-writer: her novels emerged from the world around her, and if she saw plenty of good food along with the stereotypically awful food of that time, I think we can believe her.

MM: Finally, Laura, what’s next for you? Are there any upcoming projects you’re working on that you’re able to share at the moment?

LS: I wish I knew! I'm in that nerve-wracking state of testing new ideas, discarding and revising and fiddling and re-discarding and re-revising.

MM: If people would like to keep up with your news, where can they find you online?

LS: My website is laurashapirowriter.com.

*Please note: affiliate links are used for Blackwells. If you order a book from Blackwells using one of my affiliate links, I may make a small commission from your purchase, at no additional cost to yourself. I like to support Blackwells by linking to their website, as I’m a big fan of their flagship Oxford bookshop, and they offer reasonable overseas shipping. You in turn support my work by shopping through my affiliate link. Thank you!