Father by Elizabeth von Arnim

During April, I have been immersing myself in the novels of Elizabeth von Arnim. Her most famous work, The Enchanted April,* is my Comfort Book Club choice for this month, and I’ve enjoyed other books by von Arnim in the past, most notably Elizabeth and Her German Garden and The Solitary Summer. In recent years, three other Elizabeth von Arnim novels have made their way back into print: Persephone Books republished Expiation; Handheld Press brought out The Caravaners and The British Library Women Writers series added Father to its list. I’m steadily making my way through von Arnim’s lesser known works, and Father was my most recent read.

I’m so glad that Father has been brought back into print, as it has immediately become one of my favourite books and deserves to be read much more widely. I’ve even (almost) made up my mind to pick Father as August’s Comfort Book Club choice, and it’s very unlike me to allow an author repeat within a year (let alone a few months!), but it’s hard not to want to share and discuss this marvellous novel with a wider circle. Indeed, it’s not surprising that von Arnim should be such a favourite for the book club: the lightness and charm of many of her novels make them ideal Comfort Book Club reading, whilst her superb knowledge of human nature and thoughtful commentary on women’s lives in the early 20th Century provide plenty of fodder for in-depth discussion.

Elizabeth von Arnim is an exceptional writer in her ability to combine laugh-out-loud comedy with bleaker undertones. In Father, her recurrent theme of women trapped as daughters and wives is deftly explored through a plot that at times resembles the hilarious complexity, unexpected encounters and timely match-making of the best P. G. Wodehouse stories. Jennifer Dodge is an unmarried thirty-three year old who works as an unpaid secretary for her father: typing his novels (of which everyone has heard, but hardly anyone has read), organising the smooth running of his household and letting her youth fade away. Owing to a promise made on her mother’s death-bed, Jennifer has never tried to leave her father’s house, but, on his suddenly coming home with Netta, his new (extremely young) wife, Jennifer realises she is now, finally, free to strike out on her own.

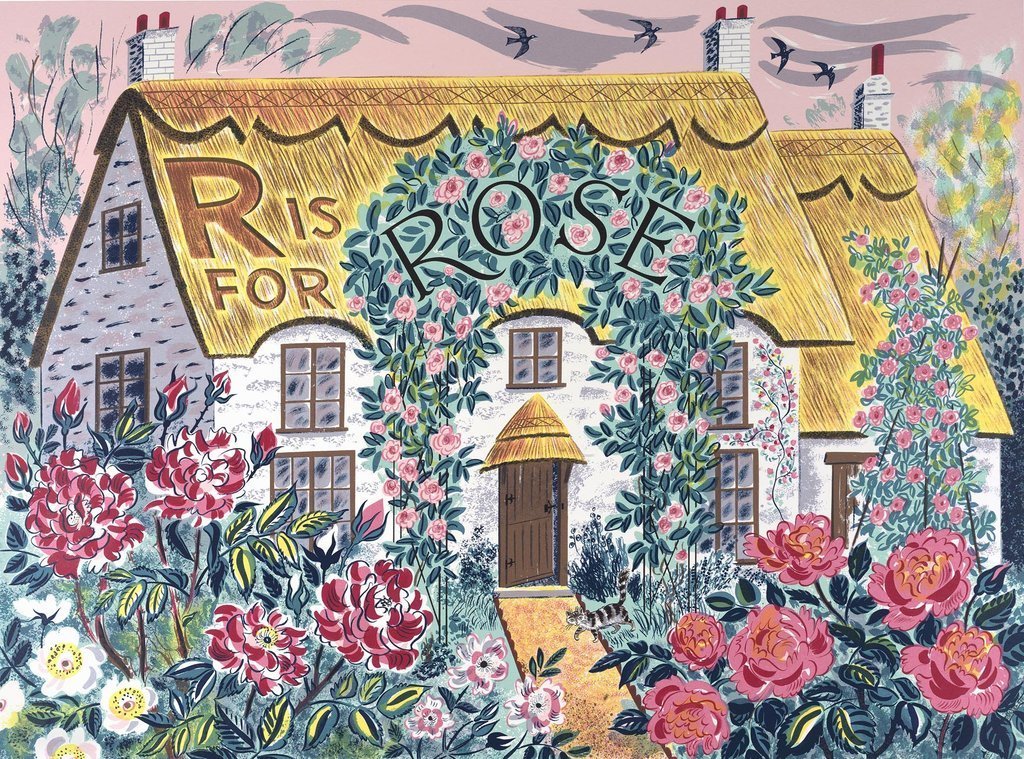

R is for Rose by Emily Sutton

Jennifer has spent her life in London yearning for the countryside and, taking advantage of her father’s absence on his honeymoon, she finds a cottage in the Sussex countryside that would surely be many people’s ideal of personal freedom:

Jen couldn’t believe her eyes when she first saw Rose Cottage — and indeed in anybody’s eyes, who should have been passing and not gone inside, it would have seemed extremely attractive. For one thing, you could hardly see it for roses; hence its name. And it had a thatched roof, and latticed windows, and a little garden with a brick path to its porch, and an orchard sloping part of the way up what she presently learned was Burdon Down, and really it was exactly like the cottages artists paint.

Was she going to get all this — the roses, the thatch, the lattice and the orchard — for five shillings a week? For about what the milk bill in Gower Street used to come to?

Even the discovery that water must be drawn from a well and that the ‘conveniences’ are housed ‘out the back’ doesn’t daunt Jennifer, who is drunk on country air and the chance of having a home (and life) of her own. And yet, Jennifer has hardly begun to enjoy her newfound freedom before complications arise: her landlord, the Rev. James Ollier, who lives with his unmarried sister, Alice Ollier, falls in love with Jennifer within the first evening of her tenancy, and Jennifer’s life is further complicated by the unexpected arrival of her new step-mother, completely unnerved by her experience of honeymooning with Jennifer’s father thus far and begging to spend the night in Jennifer’s cottage. Guiltily, Jennifer sends Netta back to her father, terrified that Netta’s distaste for married life will mean an end to Jennifer’s freedom. And when her father arrives at Rose Cottage, demanding her return to London, Jennifer must make a stand for independence, or risk losing everything she holds most dear.

Elizabeth von Arnim had a strong affinity for the natural world and escaped the demands of domestic life by immersing herself in her garden (as described in Elizabeth and Her German Garden). It is the garden that is the antithesis to the confines of an unhappy home, which Jennifer appreciates:

Jen put down the pen, and tilted back the chair, and gazed with proud and happy eyes through the green curtain of creepers at the sunlit garden beyond. Yes, and it was what life might always be, if only one broke away from the tyranny of things and people, she mused, or had the luck, as she had had the luck, to be freed from them automatically. Things and people. Houses, servants, relations, —possessions, in fact, of any sort, including somebody’s love. They smothered one; they devoured one; and long before one’s natural end, if one let them have their way, one was utterly destroyed.

Clara Cowling Gardening by Evelyn Dunbar

The garden offers another type of freedom for Jennifer: escape from worrying over her personal appearance. In Rose Cottage, she is free from the critical gaze of her father, who believes that if women cannot be pretty they should be neat. In Sussex, Jen very quickly loses her neatness: her feet and hands become blistered from walking and digging, she perspires freely in the August heat as she works in the garden and her skin tans in the sun:

[Jen] had left off being neat some days ago. Spades and neatness didn’t get on very well together, and several of her buttons had come off in moments of violent digging, and it was so nice without them, the feeling of sudden space, of lots of room for expansion was so agreeable, that she hadn’t sewn them on again.

Through the garden, Jen embraces a literal freedom from restrictive clothing, as well as the spiritual freedom from living under her father’s opinions and values. Ironically, however, much as the countryside offers a refuge for Jennifer, it also introduces another possible curtailment to her freedom: marriage. It is their mutual appreciation for the beauties of the landscape that first draw Jennifer and James together. It is in the orchard that James is set free from his inhibitions and spontaneously kisses Jennifer, and it is over the gift of a luscious basket of ripe apricots from the Vicarage garden that James first rebels against his bossy sister. Jen recognises that James lives under the same familial tyranny that she did in London, and she is determined to help him make a stand.

Orchard, Woman Seated in a Garden by Roger Eliot Fry, The Courtauld

Alice Ollier is an interesting contrast to Jennifer: she too is a spinster who resents that her life must be lived through a man. Unlike Jennifer, Alice has no desire to be left to herself; instead she has channelled her own ambitions and desires through her brother, and she is terrified that James should marry. Alice’s love for her brother is shown to be the type of affection that smothers and destroys that which it loves, but it is also hard by the end of the story not to feel in-part sorry for Alice, one of the millions of ‘surplus’ women left in the wake of WW1, who finds it almost impossible to believe that anyone but her brother should have need of or care for her.

Although Father explores darker themes of possessive love and women’s lack of freedom, it does so with a wonderful lightness of touch; many passages in the novel had me laughing aloud, and - as this is a work of fiction - von Arnim is able to tie up her characters’ stories with a very neat and satisfactory bow. However, Father does sound a warning bell, and its echo reverberates as much for readers today as it did for those at the time: independence is a gift that should not be given up easily, and only compromised for the best of reasons and the very best of love.

*Please note: affiliate links are used for Blackwells. If you order a book from Blackwells using one of my affiliate links, I may make a small commission from your purchase, at no additional cost to yourself. I like to support Blackwells by linking to their website, as I’m a big fan of their flagship Oxford bookshop, and they offer reasonable overseas shipping. You in turn support my work by shopping through my affiliate link. Thank you!