Walking in a Bluebell Wood

After a difficult April, I am more than ready to enjoy the delights of an English spring in the countryside. This is my first time experiencing the season in our new home in Yorkshire, and every week seems to bring a new marvel. In barely the blink of an eye, the trees outside my bedroom window went from faintly tinged with the yellow-lime of new growth, to a rich glossy green. Last week, I noticed bats once more swooping in the gloaming, fresh from their winter hibernation. One of my favourite things to do in the late afternoon is to walk down our narrow lane to the field at the bottom and watch the lambs gambolling through the grass. From tiny, spindly-legged white dots on the landscape, they have become much bigger and bolder, and I love to laugh over their antics as they leap into the air, ears flopping and little tails wagging.

I think the very best gift of the season, though, has been our first walk through a bluebell wood. We came across it quite by chance, going for a quiet midday stroll, when my Mum spotted a haze of blue through the trees in the distance. Native bluebells flourish in cool, damp climates and grow wild in woodlands across the UK. They are one of the nation’s most beloved signs of spring; as Fiona Stafford writes in her excellent book, The Brief Life of Flowers,* ‘Bluebells are reminders of the very origins of ‘spring,’ the great gush of life, bubbling up and spreading everywhere as April turns to May.’

I had just finished reading The Little Grey Men by B. B., and as we walked deeper into the sea of violet-blue, I felt that surely this would be the place to stumble across the last gnomes of England. There is something other-worldly about a bluebell wood; it is easy to imagine you have somehow slipped from urbane everyday life into the realms of the enchanted when engulfed in the grassy, delicately sweet scent of hyacinthoides non-scripta.

I’ve often doubted over descriptions in novels when fresh spring air is described as intoxicating and delicious as wine. Living in London, when blowing my nose left disturbing black streaks across my handkerchief, it was hard to imagine the city’s air as any kind of nectar, even if I went and breathed deeply in the middle of Hampstead Heath. Standing ankle-deep in bluebells in the Yorkshire Dales, though, I finally understood, as my lungs expanded with air honeyed by the woodland flowers.

Picking Bluebells by George Henry (1858-1943). Photo credit: William Morris Gallery.

An expanse of bluebells is generally a sign of ancient woodland (‘ancient’ meaning an area that has been wooded prior to the 17th century). This sense of walking a part of the landscape so connected to the past is perhaps what adds to the air of mystery and magic that envelops a bluebell wood, particularly if you are lucky enough to have it all to yourself. With only the sound of the birds overhead, it was easy to imagine the centuries had rolled away, and that I could come across Anne Brontë, scribbling lines of poetry on the ‘silent eloquence’ of wild bluebells that evoked pangs of homesickness and childhood nostalgia, when ‘bluebells seemed like fairy gifts.’

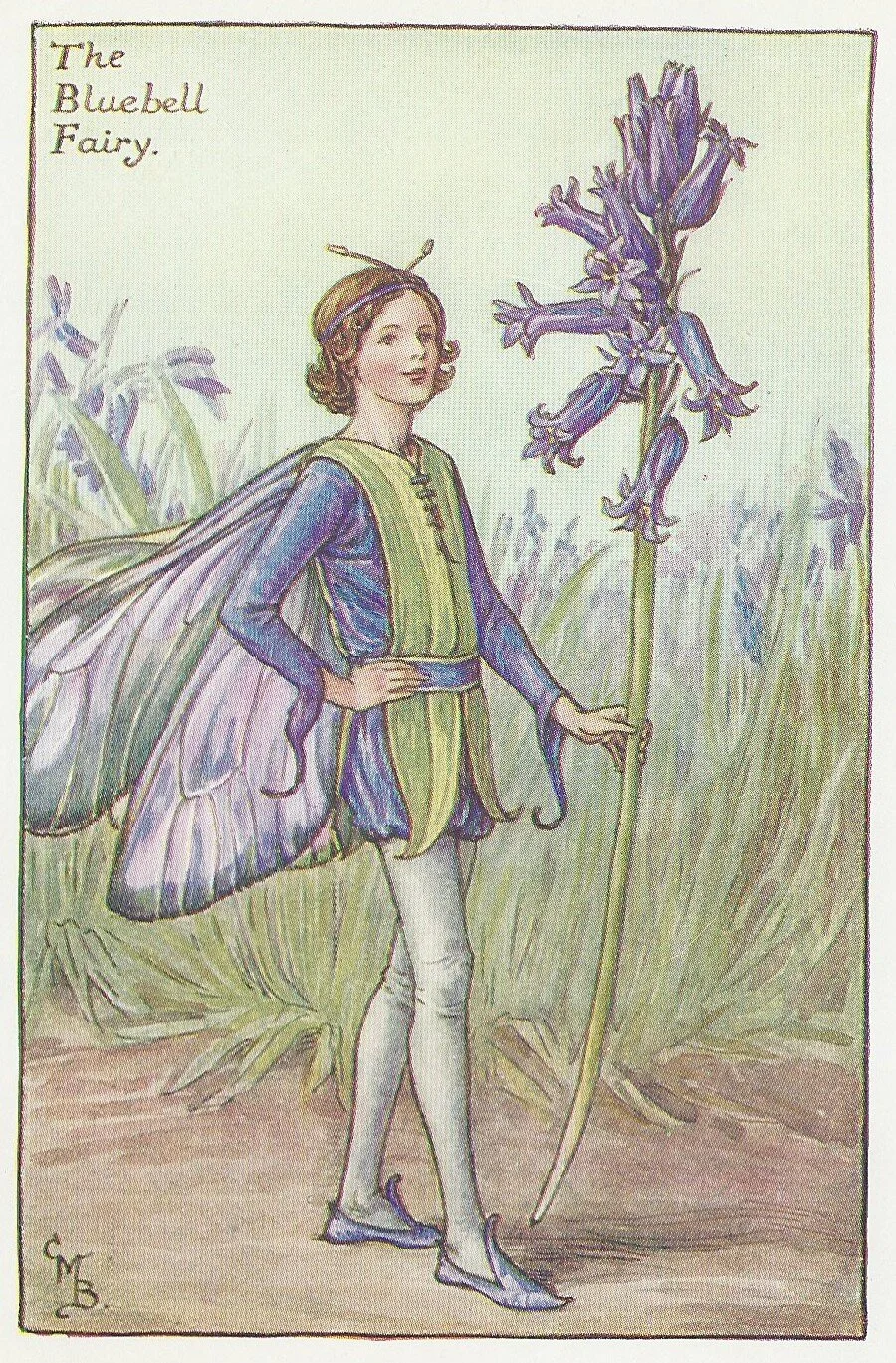

Bluebells are traditionally linked to fairy folk and old superstitions. It was believed that to hear a bluebell ringing in the woods meant a death would follow shortly after, and although ringing a bluebell could summon the fairies, only the bravest or most foolhardy would try such a trick. Certainly, bluebells do lend themselves particularly well to fairy dress, with their bell-shaped blooms and frilled petals that make such perfect caps and skirts. I love the old Dorset and Somerset names for bluebells: ‘grammer-greygles,’ ‘granfer-griggles’ and ‘granfer grigglesticks;’ words that sound so strange to modern ears that they could be the lingo of the Good People.

The Bluebell Fairy by Cicely Mary Barker. From ‘Flower Fairies of the Spring.’

Historically, bluebells were valued not only for their beautiful colour and perfume, but also for their more practical properties. The bulbs of bluebells contain a sticky substance that was used as starch to create crisp folds in linen, to attach feathers to arrows and to bind books.

Since the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981, the native wild bluebell has been considered a protected species, so they cannot be dug up or picked in the wild, and the type of bluebell you are more likely to see growing in gardens and more urbanised areas is the Spanish bluebell. This type of bluebell has a straighter stem, on which flowers blossom on either side. Flowers grow only on one side of the stem of the native wild bluebell, giving it its tell-tale bend and droop. This website gives some other useful tips for identifying bluebells.

Look for the curve and droop of the stem in native wild bluebells.

Bluebells bloom relatively early in the spring, as they take advantage of the increased light falling through trees that are only just starting to leaf, before the canopy thickens and much less sunlight can reach the woodland floor. I don’t have much time left to enjoy the bluebells before they start to fade, so I’m planning on going for a walk as often as possible in the woods near us and to use this guide by the National Trust on where is best to see bluebells blooming in Yorkshire.

*Please note, I use affiliate links for Blackwells. This means if you buy a book through my link, I may make a small commission. You won’t be charged any more for using my link, but you’ll help me to keep creating free content for you to enjoy.